- Home

- Nancy Young

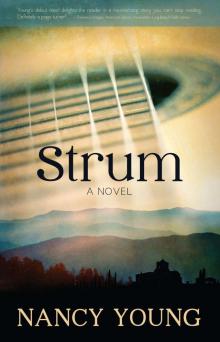

Strum Page 9

Strum Read online

Page 9

It took all her concentration to make her hands steady as she gathered her dress about her and swept gracefully into the studio. Surveying the workroom, she quickly found a low round stool a few feet in front of his work table and perched herself upon it, spreading out her skirt like a parasol. He nodded and returned to carving the large ornate jewelry box. But his heart was beating too fast and he could almost feel the small bead of sweat begin to form on his smooth brown forehead. Little butterflies began their flight in his stomach and he felt uncharacteristically self-conscious. Eventually he downed his tools and looked up, just barely finding the nerve to look back at his maddeningly beautiful audience of one. Her smile seemed to light up the darkening studio and when she stood up and brought the soft curves of her face, neck, and shoulders closer to him, it caused his whole body to riot, and the normal buzz in his eardrum to change into a stirring march.

The romance lasted for three volatile months before Lorraine began to feel she could no longer bear the young man’s silence. Together they had made a pair of polar opposites. While she had a ready and knowing smile but suffered no fools, he had a silent brooding quality that belied a gentle unassuming manner. She announced her departure by packing up her night-market trinkets while Bernard was away on an errand. Her collection of ornamental keepsakes was a catalogue of her soul — a Fabergé egg, exquisite cloisonné ring-boxes, brass camels, finger bells and toe rings acquired at the St.-Gérard markets brought to Bernard’s workshop to inspire him on her frequent but short-lived visits. She harbored a gypsy heart that could not stay in one place for long. She left him a page-long letter expressing her sadness, but resolute in her decision that it would never work.

Bernard mourned the loss of the girl fiercely but secretly, for even as he felt the emotion burn hot in the inner lining of his heart and soul, he knew he could never have kept such an exquisite creature in the cage of his secluded life. She was meant for the larger world. With time he began to feel only gratitude for having shared intimate moments with a person as exceptionally beautiful as she. After the girl, there was a procession of older women, some married and some widowed by the war, who could afford to accept his silence and even appreciate it.

•

For days after he returned from his journey into the forest of spirits, he stared at the large timber sections lying prone on his workroom floor. On his workbench lay a single slab which he had sanded and lightly oiled to discover its true color under a clean finish. The reddish gold hue and rich textured grain were mesmerizing. The lateral cut revealed a radiant core more perfectly symmetrical than he had ever seen. Its complete radiating arcs were like the rings of an onion, no irregularities marring their precise and translucent circularity.

After the fourth day the music returned and in his nightly dreams he found himself in a workshop; all around him were unfamiliar tools, grips, and vises, and his own hands appeared to be the hands of a woman. Rather than formless and timeless images as before, they were now clearly defined and absolute, and bathed in a soft warm light, the particular kind of sunlight one imagines illuminates lush mountaintops in a more temperate climate. The dreams were so real he had the sensation of working the wood with these delicate hands of his, knowing the precise pressure to use on every tool. The familiar melody now emanated from him through his own lips in a low melancholy hum. When he awoke he moved into his studio and stared for hours at the old guitar expecting it to vibrate molto appassionato of its own accord and initiate the tune that once again dominated his dreams. Only then did he realize what he had to do next.

The extraordinary timber was all and everything Bernard hoped it would be. Its tight straight grain on planing and sanding displayed a remarkable warm tone akin to the color of mead and honey. It was also miraculously free from knots and burrs and aesthetically it was like nothing he had seen before. He knew this timber was destined for objects finer than furniture or even sculpture. He imagined that the whole tree would have made an exquisite grand piano like the ones he had seen in his mother’s coffee-table books, and his only sadness now was in knowing that this could never be. But Bernard did have a guitar in his studio and it beckoned to him with its achingly familiar sunburst. After the arduous journey through the forest they travelled together, he was infinitely relieved to find it had sustained merely the slightest scratch and minimal damage from the dampness. The sheet music and manuscript however did not fare so well. Some of the hand-inked writing was lost, some of the words transferred onto the back of the page before it, and others smudged into an unintelligible blur.

Even if he could understand the writing or read the music, Bernard did not suspect they were meant for him. Nonetheless he carefully blotted everything dry and took care not to overheat the room so as not to dry the paper, parchment, leather, or guitar too quickly. The antique musical instrument stood drying separately from its case on an upright stand, and the unbound pages were laid out carefully in their original order on a long bench cut from a single piece of maple. The log had been cut into five discrete sections, two the length of his own height, two half the length of the other two, and one the thickness of a table. The diameter of each was more than equal to the width of his workbench.

Strung above his workbench between several exposed beams were the individual pages of the manuscript hung from wooden pegs like a line of laundry, or sun-bleached prayer flags in a Himalayan village. On his workbench, Bernard brought the two pairs of book-ended quarter-sawn pieces of wood together and examined their beautifully colored, mirror-imaged and perfectly straight grains, instinctively knowing that this fine-grained solid wood would make the perfect soundboard top, allowing the instruments to vibrate harmonically at perfectly true frequencies and producing a tonal quality that would be strong, dynamic, and ultimately equal to none. Without ever having played a guitar except in his increasingly vivid dreams, he knew intuitively that it would resonate with a rich, sweet, mellow sound reflective of the lively emotions he felt in his heart as he created the instruments.

He worked obsessively and intuitively, but also unhurriedly, taking each step of the construction process as if it was part of a slow sacred ritual. After a brief kiln dry, he shaped the instrument bodies as closely as possible to the images drawn in the manuscript, somewhat foreshortened from the antique guitar, which now rested in its private corner providing quiet inspiration. Near the door of the studio the old guitar stood guard, a radiant sentry with the provocative aura of a lioness, its color changing with the light that came in through the window opposite, as Bernard delicately set the decorative braided timber inlays that circled the sound hole which he had meticulously carved out of cherry and spruce and inlaid with the help of small tweezers. This elaborate design took nearly two weeks to complete but when the last minuscule piece was inserted, he felt as if he had just performed life-saving surgery on two of his closest friends.

Creating the proper hour-glass shape of the instruments presented a less exacting, but more complex challenge. He created his own methods based on the drawings from the manual and created his own freely interpreted translations of the foreign language text into his own, enabling him to construct a functional framework that turned out to be truly inspired and nearly perfect in its simple symmetry. He steamed and braced the sides as instructed and mixed and stretched the animal gut glues and strings described in the manuscript while he waited for the forms to sustain their required shapes. For the neck and headstock he shaped long pieces of silver leaf maple which he normally reserved for chair legs and arms, as their dense structure provided the required lateral and longitudinal stability and tensile strength. He sanded each neck to the exact specifications of the manuscript while feeling instinctively for the correct smoothness and a width that felt comfortable in his hands. Two carved and hand-sanded bridges and saddles were created along with twelve individual tuning keys. Satisfied with the outcome of these, he then assembled and glued all the various parts, clamping and

joining them one at a time with a whole arsenal of grips, vises, and weights. To this he applied four coats of a traditional polish to each soundboard, neck, back, and side, and hand-sanded and buffed the instruments meticulously between each coat, waiting a day to allow the lacquer to dry completely to a glassy sheen.

It had been nine months since he commenced the creation of these two masterpieces, and it was autumn again. He noticed the dried leaves fallen on his doorstep and across the expanse of his small lawn, which needed a good sweeping. Along the edge of the lake, the brightly colored leaves of the maple trees clung to the ever-denuding branches and were a welcome sight for his sore eyes. Each long day spent in the dimming light of the studio blurred his vision further. The early April sun had streamed in like a flood of spring itself when he had started the project. Keeping his studio door closed but the shades before his large windows open to the public meant that visitors arrived in a steady stream. But eventually the faces appeared less and less frequently as the project wore on and the leaves began to blow across his doorstep like brittle brown announcements of a return to cold weather and early evenings. It was a little startling for Bernard therefore to glance up one late afternoon a few weeks later to find a pleasingly familiar face pressed wanly against his window.

Lorraine had waited patiently for Bernard to complete his finishing ritual, standing back from the window as he brushed the final coat of French polish lavishly on one of the guitar bodies with a flourish of his brush, oblivious to her presence. He held the beautifully glossy instrument up for a moment to inspect the finish in the muted light, and in doing so finally noticed her and calmly focused his gaze upon her. At last moving to the door, he opened it leisurely and greeted her as if they had never parted, kissing her tenderly on both cheeks. To Bernard’s surprise she had changed little in the three years since they saw one another, albeit she seemed more beautiful than ever. He, on the other hand, had changed tremendously and was no longer the boy she once held in an innocent kiss. He had grown into a man since that time, and the maturity in his face and body brought a strange warm sensation as she gazed at him. She longed to hold him in a long intimate embrace and smell his skin or taste his lips. Those feelings surprised her for she had not come expecting to have such a strong attraction; she had only returned from a break in her university studies in Québec to visit her parents, and had planned a cordial visit to see his new studio.

Bernard sensed a difference in the way she looked at him. Her brown eyes peered up at him through her eyelashes coyly, and her lips, with their frozen smile, looked as if they were pursed for a kiss. He decided he would take the chance and leaned into her without hesitation and swept her up in his arms, carrying her into his cabin before she could utter a word of protest. With eyes resolutely closed, Lorraine let herself be carried away like a damsel into the dragon’s lair. When he laid her out on his single bed, she could only murmur a small unheard protest before he laid his body over hers and kissed her with an urgency she could understand and appreciate. At seventeen and twenty-three they had stroked intimate parts of each other’s young bodies, but respected the small-town laws of chastity before marriage. But now, after three cosmopolitan years away in the big city, the young woman was ready to embrace his manhood, and he on his part, felt a need to give her what she seemed to want.

Not long after their initial frantic love-making, they repeated the coupling once again at half the speed, taking the time to stroke each other like old lovers and tasting the strange but familiar lips. Afterward, it was Lorraine who felt the need to explain her long absence from his life. She chattered on, only partly aware that, particularly in his half-drowsy state, he would have caught but a small fraction of her words as her face turned momentarily toward the moonlight now cast through the bedroom window. The words lost on her lover didn’t seem to matter for she simply needed to exorcise the demons that haunted her after her abrupt departure years before. She had not meant to hurt him but felt the letter she left had been rather curt. It was simply easier, she had rationalized, to read her goodbye on paper rather than see it on her agitated face. They were, after all, just children back then.

The soundless banter and the vibration of her voice on his bare shoulder left Bernard feeling relaxed and joyful. He knew instinctively what she was expounding upon and just nodded earnestly whenever she sought out his face with a questioning look in her eyes. If his nod was accompanied with a smile, the result was a smile in return or huge sigh of relief. She was exorcising some sort of guilty demon or purging feelings of remorse or regret, this he knew. The confessionary look on her wide heart-shaped face in the moonlight made him think of the religious paintings he had seen on Christmas cards sent to his family. This image brought on a virtuous smile that spread joyfully across his face until it was stopped in its tracks by a barrage of kisses.

The young woman reappeared in Bernard’s life at precisely the moment the two guitars were completed. For a few days she disappeared back to her parents’ home to complete her visit, but she returned again to his rustic cabin and made it her home for nearly three weeks. All the while she harbored no expectations of him and required no reply to her complex musings on the current politics of the territory of Québec, or an answer to her many rhetorical questions about the nature of relationships and family dynamics. The mysterious age of the antique guitar was a baffling question, and she offered to research it for him on her return to the university — classical guitars were a passion of hers stemming from her days at the Catholic girls’ college at Trois-Rivières. The school had given her the opportunity to study the violin as part of her matriculation, but she was passionately obsessed with classical guitar, which was not part of the curriculum. She sought out private tutors in the myriad of older European men more than willing to share their talent and skills with her. Bernard watched her carefully inspect the delicate body of the instrument with her eyes and hands, and examine the withering sheet music and manuscript with the careful eye of a scientist.

Then, without comment or warning, she rose from her seat and dragged her chair noisily to the place where the animal gut strings were strung to dry from laundry lines across the rafters of the studio. Climbing the chair, she brought them down in one hand, smoothed them out, and quickly strung them onto the two guitars, tuning them expertly by ear and strumming them affectionately before readjusting their tuning again. She ran an eight-note arpeggio up and down each neck, amazed by the rich sound they produced even as virgin instruments. Bernard brought the sheet music to her and placed it upright on the table in front of her. She glanced nonchalantly across the score, hearing the melody in her mind, then placing one foot on a low stool in front of her chair. She held the guitar up nearly vertically as she would if dancing a tango with it, and moved her fingers over the strings to make a soulful sound like an autumn breeze tumbling leaves across a golden expanse.

Her fingers flew up and down the fret board marking out a recuerdo both passionate and lamenting, and with her other hand she plucked a rhythmic discourse with fingers moving almost inverse to the other. Her gypsy soul found a platform in the soundboard of the instrument and with it the dying embers of her passionate spirit were rekindled and stoked into a blaze. Each rising arpeggio was an ascent into the upper reaches of a Vesuvius summit and the descents a plunge into infinite sobriety. The near madness of the moving fingers felt familiar to Bernard as he watched fascinated while her hands moved autonomously seeing waves and patterns of movement within. Without thought he picked up the second guitar and instinctively strummed chord patterns in unison with her picking. Like the verses that had flowed from him in his dreams, a harmonizing strum flowed from his instrument in a rhythmic pattern not unlike the somnambulant chant of Benedictine monks. He closed his eyes, letting the waves move through his fingers, and felt the blended vibrations move into a stratosphere of vibration that broke into a metaphysical symphony of sound in his inner ear.

Lorraine had s

topped her own playing to observe with absolute awe her deaf lover play the guitar like an impassioned and seasoned musician. She had never witnessed a miracle such as this. But she was not a very devout or superstitious person, resistant to the number of miraculous “rapture” stories instilled in her by the fanatical nuns of her Sacred Heart convent school; her logical mind revolted against what she witnessed and suddenly she was overcome with dread. And then like the creature from the lake, she disappeared again, presumably back to the university to complete her studies.

He received a letter from her nearly a month later explaining that she had just been accepted into the university’s law school. She apologized for leaving so abruptly but she hated goodbyes and didn’t know how to explain to him that she was only meant to be away from her studies for a week, not the three weeks she had spent in his arms. Perhaps for the holidays she might manage to see him, but it might be a long while before she would have the chance to return to their small town. At the bottom of the page she had written: Je t’embrase, Lorraine.

He stared at her letter for quite some time admiring the steady hand in which she wrote, and memorizing every flourish of the long consonants. The writing was beautiful as he expected, and written on a sheet of pale blue linen paper enfolded in an envelope of matching texture and hue. The edges of the elegant stationery were delicately ragged, mimicking the antiquated edges of old parchment and reminiscent of the pages of sheet music he had found with the guitar. For the first time in months he thought about those papers and went to the drawer in his studio desk and pulled them out.

Strum

Strum